ARTICLES

Follow Us

Be the first to know

From Clausewitz to the Cosmos: Adapting Classical Principles to Modern Warfare Domains

By:

Arman M Nazari

President,

Global Technical Resources | Aerospace & Defense SME

Introduction

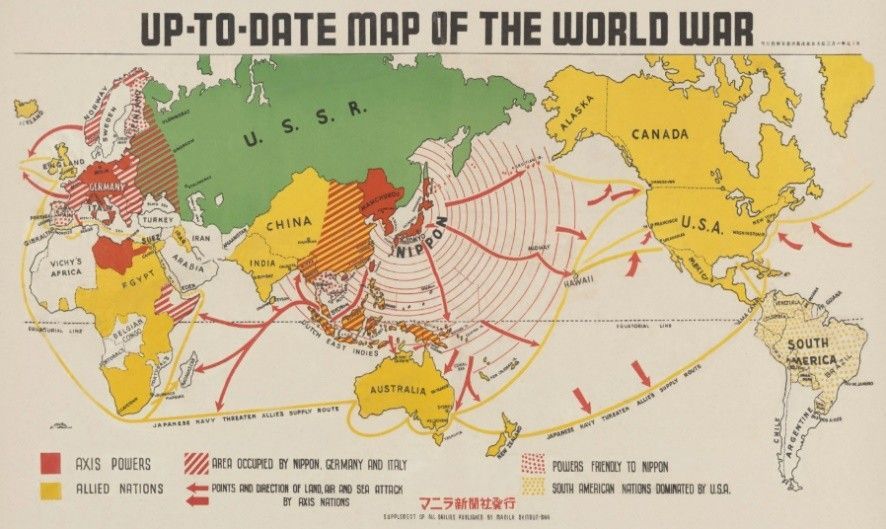

Carl von Clausewitz, the 19th-century Prussian general and seminal military theorist, is best remembered for his enduring definition of war as “the continuation of politics by other means.” He also emphasized the importance of terrain or "ground", the medium through which military force is projected. In his time, that referred mostly to the physical battlefield: land campaigns shaped by hills, rivers, cities, and seasons, as well as significant naval operations. While Clausewitz focused primarily on land warfare due to his background, his strategic vision certainly encompassed naval considerations, particularly regarding sea lanes, blockades, and maritime logistics, which were crucial to 19th-century European warfare.

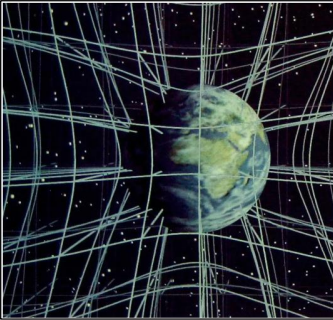

But Clausewitz’s genius lies not in the specificity of his examples, but in the universality of his logic. Modern warfare transcends the land. Today’s conflicts unfold in the air, beneath oceans, in outer space, and across cyberspace. But these new domains still obey Clausewitz’s core insight: that war is governed by the characteristics of its medium—by friction, chance, physical limits, and strategic constraints. If we reinterpret "ground" as the operational environment—whether it be saltwater, vacuum, or silicon—we unlock the true extensibility of Clausewitzian thought.

This article seeks to reinterpret Clausewitz’s core ideas through the lens of 21st-century domains: underwater warfare, aerospace, orbital strategy, electromagnetic warfare (EW), and cyberspace. I argue that Clausewitz’s framework remains profoundly relevant, offering a foundational lens through which to understand not just conventional force-on-force engagements, but also electronic, information, cognitive warfare, and the covert dimension, spying, counterintelligence, and clandestine operations. These are forms of strategic action where uncertainty, deception, and political manipulation define the battlefield as much as kinetic force.

Furthermore, Clausewitz’s concept of the defense, defined as the stronger form of war, finds modern expression in missile defense systems like THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense), Arrow, and Patriot. These systems are not merely technological marvels; they are shaped by the Clausewitzian logic of protecting critical centers of gravity, such as population centers, command infrastructure, or deterrent capabilities. The deployment and posture of such interceptors mirror Clausewitz’s idea of defending key terrain. Likewise, strategic deterrence via ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles) or survivable second-strike systems follows his notion of war as a political instrument, calibrated for escalation control. Programs like the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) were rooted in the same strategic calculus: deny adversaries the confidence of offense and thereby constrain political options.

I. Clausewitz’s 'Ground': Medium as Battlespace

1. Classical Concept of Ground

Clausewitz wrote in a time when ground-based maneuver was the heart of warfare. In his work On War, he emphasized:

- The importance of occupying advantageous terrain.

- The influence of seasonal and environmental conditions on campaign viability.

- The limits imposed by geography, logistics, and communication.

Yet Clausewitz’s “ground” was never merely literal. It was the

medium of decision-making and contest, the physical, psychological, and political landscape through which military force maneuvered.

2. Ground as Environment

Reframing “ground” as any domain governed by unique physical and tactical constraints allows Clausewitz to speak directly to:

- Subsurface warfare where sonar and stealth dominate.

- Air and space warfare shaped by electromagnetic clarity and orbital dynamics.

- Cyber operations are shaped by bandwidth, code latency, and cloud topology.

II. Underwater Warfare – Clausewitz Beneath the Surface

1. Acoustic Terrain

In the undersea domain, the ocean’s thermodynamic properties replace hills and valleys.

- Thermoclines: Layers of rapid temperature change scatter sonar beams, creating "acoustic shadows" akin to valleys where enemy subs can hide.

- Salinity gradients: Alter sound propagation in unpredictable ways.

- Seasonal and geographic variations: In winter, polar oceans offer different acoustic properties than equatorial waters.

2. Strategic Application

- Nuclear Deterrence: Submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) platforms rely on hiding in such acoustic terrain.

- ASW (Anti-Submarine Warfare): Relies on predicting and mapping these dynamic underwater terrains.

- Clausewitz's principle of exploiting environmental advantage directly applies to submarine patrol routes and intercept corridors.

III. Airpower – Friction in the Skies

1. The Sky as Medium

While air warfare removes ground friction like terrain, it adds others:

- Jet streams and turbulence alter flight paths and fuel efficiency.

- High-altitude weather affects UAV and satellite performance.

- Cloud cover and electromagnetic conditions impact ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance).

2. Electromagnetic Fog of War

- EW (Electronic Warfare) creates synthetic fog, disrupting radar, GPS, and communications.

- ECM/ECCM (Electronic Countermeasures / Counter-Countermeasures) form the evolving duel of deception.

- Clausewitz's concept of “fog and friction” extends here, disorder isn’t just physical but electromagnetic.

3. Case Study

In Operation Allied Force (1999), Serbian forces used radar deception to confuse NATO strikes, proving that air dominance still depends on understanding and manipulating the environment.

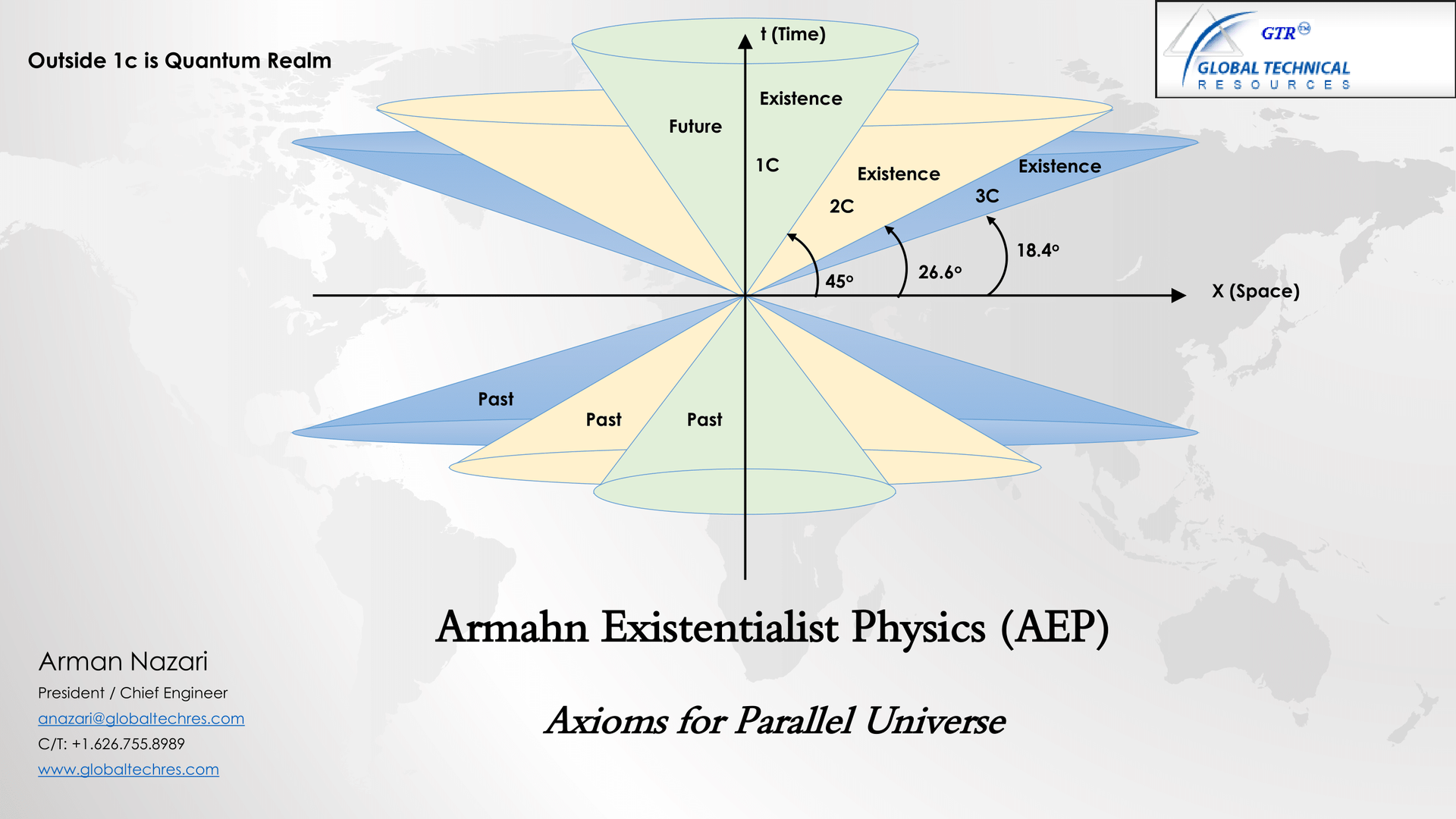

IV. Space – Clausewitz in Orbit

1. Orbital Ground

- In space, the terrain is made of orbital paths, Lagrange points, and gravitational assists.

- Orbital slots around Earth and the Moon are limited, like narrow valleys.

- Timing of burns and launches defines maneuver windows, akin to weather.

2. Strategic Depth

- Control of cis-lunar space (between Earth and Moon) is emerging as a priority.

- Lunar South Pole: China and the U.S. seek control due to permanent shadow zones for ice mining.

- Clausewitz’s principle of the center of gravity applies: In space, this could be a satellite constellation or logistical depot.

3. Warfare Characteristics

- No cover: Everything is visible unless using stealthy trajectories or jammers.

- Debris and Kessler Syndrome: Creates lasting environmental friction.

V. Cyber and Cloud – Clausewitz in the Net

1. Digital Terrain

- Data centers, cloud architectures, and network latency are the terrain.

- Bandwidth congestion, firewall placement, and fog computing create "choke points."

- Clausewitz’s emphasis on

lines of communication mirrors digital routing paths.

2. Attack Vectors

- DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service): Like carpet bombing of a highway network.

- Supply chain exploits: Analogous to poisoning logistics lines.

- Zero-day exploits: Like hidden passes in mountain ranges.

3. Strategic Cyber Clausewitz

- Clausewitz’s center of gravity = DNS root servers, critical firmware, cloud infrastructure.

- Friction = code incompatibility, patching lags, human error.

- Fog = misinformation, identity spoofing, sensor disruption.

VI. Intelligence and Electromagnetic Maneuver

1. Sensor Networks as Clausewitzian Eyes

Clausewitz emphasized

knowledge gaps. Modern equivalents include:

- ELINT (Electronic Intelligence): Radar emissions.

- SIGINT (Signal Intelligence): Comms interception.

- CGINT (Cloud Geospatial Intelligence): Mapped digital terrain and physical networks.

2. EW and Control of Perception

- Warfare is not only force projection but sensor denial and deception.

- Cyber-electromagnetic activities (CEMA) form a modern fog of war.

- Active camouflage in radar and optical domains.

3. Covert Operations and Espionage

- Clausewitz acknowledged war’s political nature and its use of subversion. In today’s warfare, covert operations, espionage, and counterintelligence are force multipliers.

- Human Intelligence (HUMINT) and covert action are the terrain of shadow wars.

- Just as Clausewitz studied morale and deception, today’s strategist must master narrative control, psychological operations (PSYOP), and clandestine disruption.

VII. Clausewitz’s Strategic Continuities

1. Center of Gravity (CoG)

- Then: Capital city, king, or main army.

- Now: GPS satellites, space logistics hubs, carrier strike groups, submarine cables.

2. Friction

- Then: March delays, bad maps.

- Now: Data latency, signal jamming, cyber exploits, AI hallucinations.

3. Fog of War

- Then: Smoke, terrain, confusion.

- Now: Misinformation, spoofed signals, deepfakes, AI-generated traffic.

4. Genius and Initiative

- Clausewitz stressed that “military genius” is not about brilliance but the ability to act in uncertainty.

- In AI-dominated battlefields, human judgment in the loop remains critical where Clausewitz’s "genius" adapts not only to what is known, but to what is unknowable.

Conclusion: A Clausewitz for All Domains

Clausewitz never wrote about stealth fighters, hypersonic missiles, or orbital battle stations. But his philosophy of war, defined by friction, environmental constraint, political purpose, and dynamic interplay, remains remarkably applicable. By recognizing that each domain has its own “ground,” its own constraints and frictions, we can bring Clausewitz fully into the 21st century.

To study war in the modern age is not to abandon Clausewitz, but to evolve him. War remains the continuation of politics, but now through a multitude of means: acoustic, orbital, digital, and electromagnetic. The commander who master’s these terrains, not just individually but in harmony, will be the true strategist of the 21st century.

Let us, then, not ask what Clausewitz would have said about satellites or cyber-attacks but instead, ask what timeless principles he left us to interpret, adapt, and apply anew.

Carl von Clausewitz in Prussian service; portrait by Wilhelm Wach, early 1830s