ARTICLES

Follow Us

Be the first to know

Iran's Victory Bridge: A Hegelian Lens on the Anglo-Soviet

Invasion and Reza Shah's Foreign Policy

By:

Arman M Nazari

President,

Global Technical Resources | Aerospace & Defense SME

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Iran was caught between two great imperial powers,

Britain and

Russia, locked in a geopolitical struggle known as the

Great Game. For the British Empire, Iran was a critical buffer for protecting India, while the Russian Tsars viewed Iran as a gateway to the warm waters of the Persian Gulf. This historic rivalry set the stage for Iran’s later entanglement in World War II, where ideology, pragmatism, and shifting alliances collided in a decisive moment.

By the 1930s, under Reza Shah Pahlavi, Iran embarked on a policy of modernization and independence. Determined to escape imperial manipulation, Reza Shah pursued a neutralist foreign policy, deliberately limiting British and Soviet influence while seeking new partnerships, most notably with Nazi Germany. Germany, lacking colonial ambitions in Iran, became an attractive partner. German engineers, technicians, and companies were welcomed to help modernize Iranian industry and infrastructure. In Hegelian terms, Britain and the USSR were seen as the Thesis and Antithesis, historical forces pulling Iran in opposing directions. Germany emerged as a Synthesis, a third path Iran believed could ensure sovereignty without imperial domination.

Reza Shah’s Intentions: Pragmatism, Not Ideology

It is essential to clarify that Reza Shah Pahlavi was not a Nazi sympathizer, nor was his alliance with Germany rooted in shared ideology. Rather, his foreign policy was shaped by deep mistrust of colonial powers, derived from decades of British and Russian interference in Iranian affairs. Germany, lacking a colonial past in the region, offered a neutral partnership centered on mutual economic interests. German firms assisted in constructing modern infrastructure, including railways, factories, and roads. German advisers helped develop Iran’s banking and educational systems, and plans were underway for joint ventures in mining and oil refining.

Reza Shah’s pragmatism extended to humanitarian concerns as well. According to accounts from wartime Europe, Iranian diplomatic missions, particularly in France, quietly helped Jewish refugees. The Iranian embassy in Paris reportedly issued falsified Iranian passports to Jews

attempting to flee Nazi-occupied territories, helping them avoid deportation and gain safe passage. These actions were consistent with the Shah’s broader goal of preserving Iranian dignity and neutrality, even in the face of intensifying global conflict.

Faced with the reality of foreign invasion, Reza Shah chose abdication over resistance to avoid the devastation of his country. He stepped down voluntarily on September 17, 1941, under pressure from the Allies, but with the intent to preserve Iran’s territorial integrity and prevent bloodshed. In that decision, he prioritized national survival over personal power—an act often overlooked in discussions of his wartime legacy.

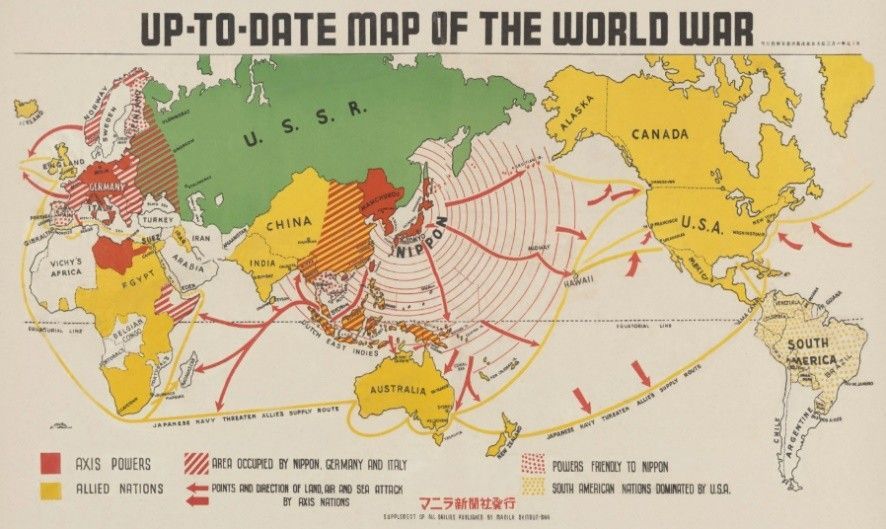

German Ascendancy: Betting on a Winning Horse

Iran's alignment with Germany was not irrational. By 1941, Nazi Germany appeared unstoppable:

• Sept 1, 1939: Germany invades Poland (WWII begins)

• April - June 1940: Germany conquers Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Netherlands, and France

• Oct 1940, Apr 1941: Germany aids Italy in Greece and invades Yugoslavia

• June 22, 1941: Launches Operation Barbarossa, a massive invasion of the Soviet Union

By August 1941, German forces were perilously close to achieving total dominance over the Soviet Union. Army Group North had surrounded Leningrad, beginning what would become a brutal 872-day siege. To the south, Army Group South threatened Kyiv, and most critically, Army Group Center had advanced within 200 miles of Moscow, defeating Soviet forces at Smolensk and preparing for Operation Typhoon, the assault on the Soviet capital. From Tehran’s perspective, the Soviet Union seemed on the brink of collapse. Betting on Germany appeared to be a calculated move aligned with geopolitical momentum.

The Dialectic Reversed: From Synthesis to Antithesis

In June 1941, with Operation Barbarossa, the Thesis and Antithesis, Britain and the USSR, merged into a wartime alliance against Nazi Germany. Germany, once Iran’s neutral partner and effective Synthesis, was recast as the new Antithesis. Iran’s continued relations with Germany, including its refusal to expel German nationals, now appeared threatening to Allied interests. The Iranian government failed to adjust quickly to this transformation. Consequently, the UK and USSR jointly invaded Iran on August 25, 1941, to secure oil fields and protect the Persian Corridor, a supply route critical for supporting the Soviet war effort.

Military Disparity: Iran vs. the Invading Forces

When the Anglo-Soviet invasion commenced in August 1941, Iran’s military was vastly outmatched. The Iranian army, numbering approximately 126,000 troops, was poorly equipped and lacked modern armor and air power. In contrast, the invading forces brought overwhelming

superiority:

- British Commonwealth Forces (from Iraq and India): ~70,000 troops, with modern tanks, artillery, and air support

- Soviet Red Army (from the Caucasus): ~45,000 troops, including mechanized infantry, tanks, and aircraft

Combined, the invading forces totaled over 115,000 well-armed troops, supported by dozens of fighter planes and armored vehicles. Iran’s resistance was limited to scattered engagements, primarily in Khuzestan and Azerbaijan. Despite brave pockets of defense, the disparity in

military capability made sustained resistance impossible.

The Occupation and the "Victory Bridge"

The Anglo-Soviet invasion lasted less than a month:

- August 25, 1941: Anglo-Soviet forces enter Iran

- September 17, 1941: Reza Shah is forced to abdicate in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Iran’s territory became the "Victory Bridge"—a vital supply line for the Allied war effort:

- 1941–1945: The Persian Corridor served as a key route for the U.S. Lend-Lease Program, delivering military aid and supplies to the USSR

- Over 5 million tons of goods—including trucks, planes, tanks, food, and raw materials— flowed through Iran

- This logistical support played a crucial role in the Soviet defense during the Battle of Stalingrad and subsequent counteroffensives

The centerpiece of this corridor was the Trans-Iranian Railway, a 1,394-kilometer line stretching from the Persian Gulf port of Bandar Shahpur (now Bandar Imam Khomeini) to the Caspian Sea port of Bandar-e Torkaman. Originally built with significant technical assistance from German

engineering firms in the 1930s, the railway was a modern marvel that became the backbone of Allied logistics. After occupation, the U.S. Army Transportation Corps and British engineers upgraded and expanded the railway to handle the immense load. At peak operation, over 10,000

tons of supplies per day moved through Iran, including Studebaker trucks, C-47 aircraft parts, locomotives, medical supplies, and ammunition—all vital for the Red Army’s endurance and counterattack.

Turning the Tide: Stalingrad and Beyond

• August 23, 1942: The Battle of Stalingrad begins

• February 2, 1943: Ends with German defeat, turning point of WWII on the Eastern Front

• The supplies from the Persian Corridor helped the Red Army stay armed and fed during the harsh winter and siege conditions

• Post-Stalingrad: Soviet forces begin pushing westward, retaking territory and shifting the balance of the war

Geopolitical Synthesis: The Rise of the United States

With Britain weakened and the USSR bloodied, the United States emerged as the new global Synthesis:

• Became the principal supplier of material aid to both Britain and the USSR

• Took on a leadership role in shaping the postwar order

• Hosted the Tehran Conference in 1943, where Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin met in Iran to coordinate strategy

Iran, meanwhile, found itself at the heart of Allied logistics and diplomacy. Though occupied, it gained new geopolitical relevance and laid the groundwork for increased U.S. influence in the Middle East.

Conclusion: The Fluidity of Dialectics in Global Politics

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in 1941 was not just a military operation, it was a dialectical rupture. What Iran had perceived as a balanced triangulation between hostile powers was swept away by the new wartime alliance. In Hegelian terms, Thesis and Antithesis are not fixed, they shift with historical necessity. When Britain and the USSR fused into a wartime Thesis, Germany, once the neutral Synthesis, became the Antithesis. And from the wreckage of that shift, the United States emerged as the new Synthesis, offering Iran and the world a redefined

postwar reality. Iran’s failure to adapt to this dialectical transformation resulted in occupation and loss of autonomy, but also in its transformation into the Victory Bridge that helped change the course of the Second World War.

Postwar Compensation and Unresolved Legacy

In recognition of Iran’s strategic role and wartime sacrifices, Iran officially joined the Allied cause in 1943. As a result, both the United States and the Soviet Union compensated Iran for the use of its territory and infrastructure. The USSR, in particular, paid Iran partially in gold bullion,

honoring its commitments to postwar reparations. However, the United Kingdom never formally compensated Iran for its share of the occupation or the economic toll exacted during the war. To this day, the issue remains a point of historical grievance in Iranian national memory—reflecting

the uneven legacies of wartime alliances and the complex moral balance of power politics.

A lesser known but significant postscript to this legacy involves Reza Shah’s pre-war industrial vision. In the late 1930s, Iran contracted with German firms to construct a 15,000-ton steel mill, initially planned for Varamin and later relocated to Karaj. As part of the deal, Iran reportedly made partial payments in agricultural goods, including wheat. The German equipment was fabricated and en-route when WWII erupted. However, following the Anglo-Soviet invasion, British forces seized the shipments in the Mediterranean, storing them in Egypt for the duration of the war. After the conflict, the equipment that finally reached Iran was damaged, rusted, and incomplete, rendering the project unviable.

Some anecdotal accounts suggest that the confiscated machinery may have been redirected to British-controlled India, possibly benefiting the early foundations of Tata Steel. Yet, no documentary evidence has substantiated this claim. While the story persists in some oral histories, it remains speculative. Nevertheless, the episode underscores the vulnerability of smaller nations to great power politics, where strategic infrastructure could be derailed, or even repurposed, without recompense.

In recognition of Iran’s strategic role and wartime sacrifices, Iran officially joined the Allied cause in 1943. As a result, both the United States and the Soviet Union compensated Iran for the use of its territory and infrastructure. The USSR, in particular, paid Iran partially in gold bullion,

honoring its commitments to postwar reparations. However, the United Kingdom never formally compensated Iran for its share of the occupation or the economic toll exacted during the war. To this day, the issue remains a point of historical grievance in Iranian national memory, reflecting

the uneven legacies of wartime alliances and the complex moral balance of power politics.

Reza Shah Pahlavi and his son

Trans Iranian Railway

Invasion of Iran

Anglo Soviet Troops